Protein First: A Sensible Shift, With Caveats

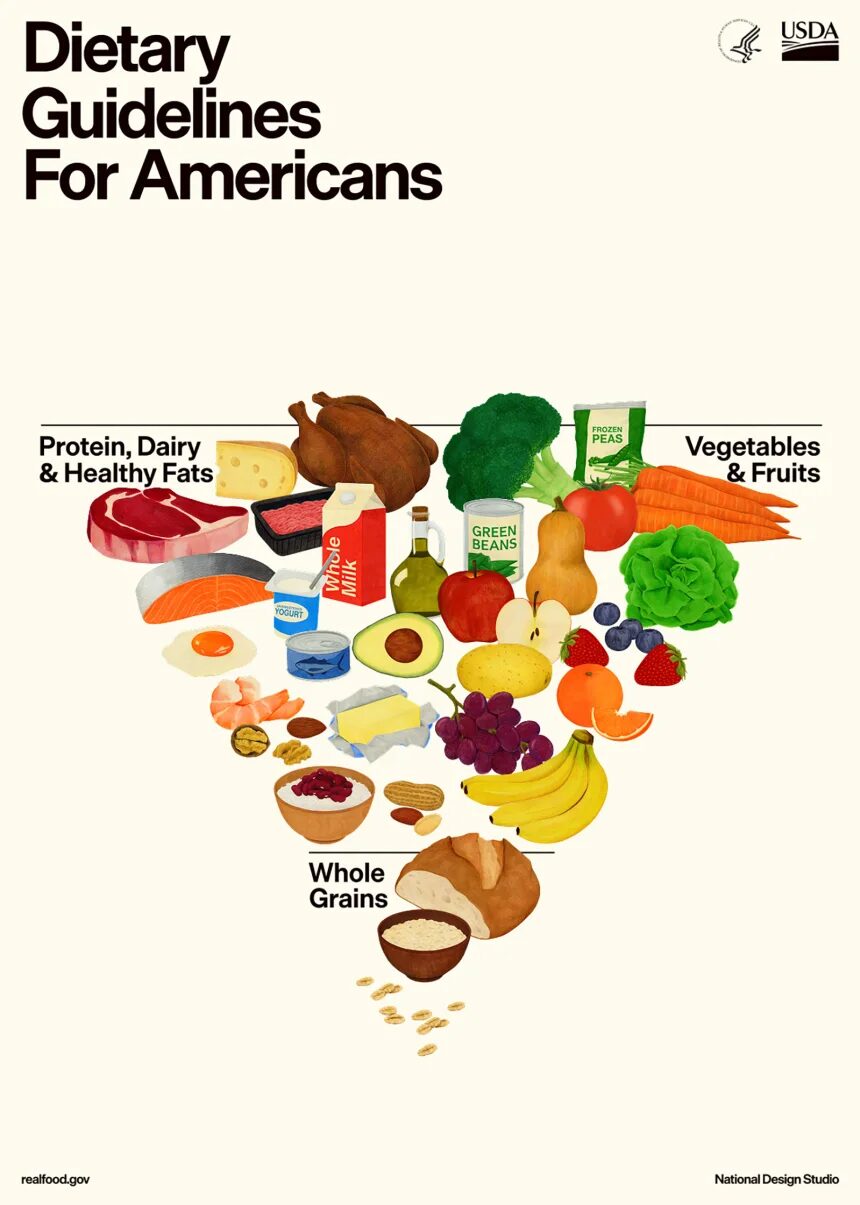

One of the most notable changes is the emphasis on including protein at every meal, from a variety of sources, without restricting recommendations to lean protein alone. This aligns with evidence supporting protein’s role in muscle maintenance, satiety, metabolic health, and healthy ageing (2, 3).

That said, the Guidelines retain a 10% upper limit for saturated fat intake, creating a practical tension. Encouraging higher protein intake without clearly guiding food choices may make it difficult for many individuals to meet both targets simultaneously, particularly if protein is sourced primarily from fatty meats and full-fat dairy.

From a genetic standpoint, this matters. Variants in genes involved in lipid metabolism, such as APOA2 and PPARG, can influence how individuals respond to saturated fat, with some people experiencing disproportionate increases in LDL cholesterol and cardiometabolic risk when intake is high (4). While whole foods are preferable to processed alternatives, “real food” does not affect everyone equally.

Dietary Fat: Acknowledging Uncertainty Is Honest Science

The Guidelines take a more neutral stance on dietary fat, acknowledging that healthy fats are present across many whole foods, including meat, eggs, seafood, nuts, seeds, olives, avocados, and full-fat dairy. Importantly, they also state that more high-quality research is needed to clarify which types of fats best support long-term health.

This admission reflects scientific reality. Despite decades of research, the relationship between saturated fat and cardiovascular disease remains complex and highly individual (5). Genetics, baseline metabolic health, overall diet quality, and food context all modify risk.

The key advancement here is not declaring any fat category “good” or “bad,” but recognizing uncertainty is a necessary step toward more nuanced, evidence-based nutrition guidance.

Carbohydrates: Quality Matters, and So Does Individual Response

One of the strongest and most constructive aspects of the updated Guidelines is the clear directive to significantly reduce ultra-processed and refined carbohydrates while prioritising whole, fiber-rich foods and home-prepared meals. Reducing reliance on packaged breads, ready-to-eat cereals, crackers, sweets, and sugary snacks is an unequivocal public health win.

Where nuance becomes essential is in how individuals respond to carbohydrates, even when those carbohydrates are relatively “normal” or culturally common foods.

From a nutrigenomics perspective, genetic variation influences glucose metabolism and insulin response. Certain gene variants involved in insulin signalling and glycaemic control, such as those associated with TCF7L2, are linked to increased sensitivity to rapidly absorbed carbohydrates, translating into a higher risk of dysglycaemia and type 2 diabetes for some individuals (6). For others, the same foods may be metabolically neutral, particularly when consumed with adequate protein, fiber, vegetables, and healthy fats.

This does not mean carbohydrates like rice or grains are inherently harmful. Rather, it highlights that tolerance varies, and context matters. Portion size, food combinations, activity level, and genetics all influence metabolic outcomes (7).

What is clear – without genetic caveats – is that ultra-processed carbohydrate-rich foods consistently worsen metabolic health and should be minimised across the population.

Sodium, Alcohol, and Individual Sensitivity

The Guidelines reaffirm sodium intake limits for the general population while acknowledging that highly active individuals may require higher intake to offset sweat losses. This balanced view is appropriate but again, genetics plays a role.

Some individuals are salt-sensitive, meaning higher sodium intake leads to disproportionate increases in blood pressure, while others show minimal response (8). Alcohol guidance follows a similar pattern: less is better for overall health, though individual risk varies based on genetics, sex, and metabolic capacity.

The Bigger Picture: A Public Health Reset, Not a Universal Prescription

Ultimately, these Guidelines are clearly designed to address uniquely American and Western dietary challenges: high fast-food consumption, ultra-processed food accessibility, excessive sugar and sodium intake, and declining metabolic health. In that context, the emphasis on real food, protein adequacy, and reduced processing is both necessary and overdue.

However, it is important to recognize that population-level guidelines cannot replace individualized decision-making nor should they be universally applied across cultures with very different dietary traditions and health profiles.

The next step in nutrition policy isn’t to scrap guidelines, but to make them smarter. Recognizing genetic and metabolic differences acknowledges a simple truth: the same food doesn’t work the same way for everyone. That’s not a failure of nutrition science but it’s simply how it evolves (9).

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & USDA. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030 (Draft / 2026 Update).

2. Phillips SM, Van Loon LJC. Dietary protein for athletes. J Sports Sci, 2011.

3. Wolfe RR et al. Optimal protein intake in older adults. Aging Res Rev, 2017.

4. Ordovás JM, Corella D. Nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics. Curr Opin Lipidol, 2004.

5. Siri-Tarino PW et al. Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr, 2010.

6. Cornelis MC et al. TCF7L2, carbohydrate intake and diabetes risk. Diabetes Care, 2009.

7. Zeevi D et al. Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell, 2015.

8. Elijovich F et al. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure. Hypertension, 2016.

9. Ordovás JM et al. Personalized nutrition and health. BMJ, 2018.